The history of football is the history of powerful men messing up. The manager, maybe, or an expensive new signing: more often than not, the owner. He loses Brian Clough or fails to harness the Premier League boom. Perhaps he takes a £100million punt with money he does not have. And these mistakes echo through time.

There will be a reason it began to go wrong for Huddersfield Town after 1926, why Wolverhampton Wanderers have never recaptured their Billy Wright era heyday and the first championship and FA Cup double of the 20th century turned out to be the last league title that Tottenham Hotspur won.

In recent times two significant things happened to usher in the Manchester United years: SirAlex Ferguson left Aberdeen to reinvigorate Old Trafford, and Liverpool lost direction and economic clout, making errors of judgment from boardroom to boot-room. One club rose, the other fell. That is the narrative of football. If it were not, we would quickly lose interest.

Some years ago, after running United close in a game at Old Trafford, Gerard Houllier, then Liverpool manager, looked around the stadium with a half-smile. ‘The wonderful thing with football is that nothing lasts forever,’ he said. And while for a Liverpool supporter still waiting for that first title of the modern era it might not feel that way, what Houllier said is true.

One day Ferguson will leave, or somebody at Manchester United will mess up big time, and then it will be the turn of another club.

Ferguson’s achievement, in his words, was to knock Liverpool ‘right off their ****ing perch’ and there are now managers plotting to do exactly the same to him.

That chance may come sooner than expected if the dark speculation concerning United’s financial future is correct. The jury is out on just how much trouble the club are in, largely because there are parts of the Pyramid Texts that are easier to decipher than Manchester United’s accounts, but the most doom-laden interpretations paint the Glazer administration as emblematic of the global banking system, a castle built on sand, laden with unsustainable debt and vulnerable to the whims of the market.

And while this may be bad news for United and those who care for them, if a spokesman was appointed for the 91 other clubs, the ones who do not get 75,000 fans through the gate, are not champions of England, champions of Europe, as the song goes, and have not come to dominate a moment in football like none before, that mouthpiece would say: Good.

Just as the rest of football did when Liverpool faltered — conveniently ignoring the fact that part of that misstep was a reaction to the Hillsborough tragedy. Just as it did when Roman Abramovich’s investment in Andriy Shevchenko blew up in his face by forging the rift with Jose Mourinho, the former Chelsea manager.

This is how football evolves. It is not always fair and the supporters of a club that loses a good manager, a good player or puts a fool in charge of the company float are the sorry collateral damage, but this has to happen for there to be progress.

The most destructive element of the Champions League is that UEFA’s money, given to disproportionately few, makes it even harder for a big club to fail. It requires something that is, in sporting terms, truly catastrophic for evolution to occur; something like saddling a club with unmanageable debt, maybe.

The reason it is hard to damn the Glazers on all fronts just yet is because they have presided over fantastic sporting success as custodians of Manchester United. They have let the football people run the football, kept their heads down, their mouths shut and paid up when asked, often in circumstances when others would not (when buying Michael Carrick and Owen Hargreaves, for instance).

The Glazers are negatively compared to United’s plc board because English football has this bizarrely nostalgic idea that there was a golden age of club ownership, but the plc would not have sanctioned expensive bids for two English squad players operating in basically the same position, as Malcolm Glazer did.

Quite probably, it would have sold Cristiano Ronaldo last summer, given an £80m offer, and hid behind responsibility to shareholders and the player’s desire to leave. (Yes, the plc board always fended off interest from Italy in the young Ryan Giggs, but to accept the money at that stage would have meant selling the player against his will and probably losing Ferguson in the process. Whatever was on offer, there was no option but to resist)

What is also forgotten is that private ownership is best in an industry governed by factors as variable as refereeing decisions, injuries and fatigue. For instance, the year that Manchester United exited the Champions League at the group stage against Benfica, the Glazers simply got on a plane and returned to America without uttering a word. No panic, no crisis, and the title was back at Old Trafford within 18 months.

Had United been a plc at that time, a statement would have been made, perhaps a profit warning. Certainly there would have been a fall in share price (as there would have been in the current economic climate, making the sale of Ronaldo inevitable, rather than possible).

So, while there are many faults with the Glazers, United’s previous economic model was hardly ideal, and the fact is that when a business that is so vast is reliant on the brilliance of one man,

Ferguson, who is past retirement age, trouble is always lurking around the corner. Why do you think media analysts are so intrigued by the future of Rupert Murdoch’s empire?

It is not a case of wanting Manchester United to fail. Nobody who loves football should want them to fail. They play exhilarating, entertaining football, produce outstanding young players, fly the flag for the English game in Europe and beyond and have a large, passionate following that endured mediocrity for too long.

If, however, the edifice that Ferguson built begins to crumble beneath the weight of corporate debt, tough. That is the way football goes.

Tottenham had huge financial problems linked to mistakes made in diversification in the late Eighties; West Ham United could still be under threat due to the collapse of the Icelandic banking sector. These are the breaks. Nobody has the right to support a team from a position of strength all the time.

Those painting Manchester United’s future as a calamity for the wider game miss the point. A football club must be right on the field, and off the field. The test is to strike the balance between sporting ambition and sensible business practice and, if either element is wrong, failure will result.

Go back to the original Carlos Tevez ruling at the Premier League tribunal and the reason the decision was flawed was that it took the emotions of the West Ham supporters into account above the need for a business to be run properly. Had West Ham been deducted points and effectively relegated, it would have been rough on the fans, but they could have gone to the end of a long line of people who feel bitterly let down by the executives of their football club. Join the queue: Southampton, Leeds United, Nottingham Forest, Leicester City, the lower leagues are full of them.

And in this way, football ebbs and flows. If it did not, if no rich men were ever allowed to make mistakes, to sell good players, to lose good managers, to concoct a business future on foundations of quicksand, the same clubs would win the league every year.

As painful as it may seem, we need hare-brained teams comprising galacticos, we need Bayern Munich to give the job to Jurgen Klinsmann or for the Glazer family to be manoeuvred into buying Manchester United rather than selling their shares at top price, because that is what makes the sport so enthralling.

If the Glazers have got it as wrong as has been suggested, Manchester United’s rivals should wish them well, rather than discourage. The best advice is from Napoleon. ‘Never interrupt your opponent when he is making a mistake,’ he said.

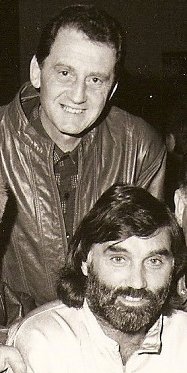

With George Best in 1991

With George Best in 1991

Recent Comments